"You Must Choose..." Thoughts on Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade

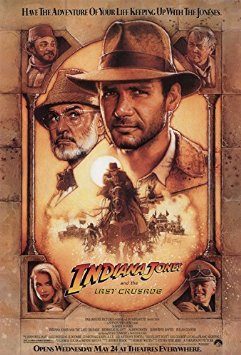

Image: poster for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade

I have a very complicated relationship with my biological father. My parents divorced early in my life, and I rarely saw my father growing up. We lost touch for nearly a decade, until we reconnected a few years ago after finding each other on Facebook. Personal reasons kept him out of my life (which I won’t discuss here), but meeting him again after I had become an adult was bittersweet.

I have only seen two Indiana Jones movies in theaters, and it’s the one without the monkeys and flesh-eating ants. It is also, and I write this with some trepidation for the comments that could follow, my favorite of the entire franchise. Yes, Raiders of the Lost Ark is perfection on celluoid, but Last Crusade is meaningful for two personal reasons. My relationship to my father was one. (I’ll get to the second reason below.)

Dr. Henry Jones, Sr. was a distant father from Henry Jr., too distracted with a personal quest for the holy grail to notice his son had stolen the Cross of Coronado from a band of grave robbers. Henry Jr., nicknamed Indiana, became as opposite to the bookish, homebound Henry Jones Sr. as he could become, reuniting only years later when the Nazis abduct the older Jones in an effort to find the grail.

My father is a painter and graphic artist, a man with such a bohemian spirit he lived on a boat for years at sea. If my father is Indiana Jones, I’m Dr. Henry Jones: domestic, studied, obsessive. I was taught that I shouldn’t be like my father, and I tried very hard not to be growing up.

Eventually, our similarities were too hard to ignore. Like both Dr. Joneses, our underlying natures are the same: we’re both creative types, though expressed in very different ways.

I watched Last Crusade again about a week ago, as I’m on an Arthurian legend kick. Of the original films, it’s the least problematic in terms of racial depictions (and don’t get me started on Temple of Doom, which I enjoy less than the underrated Crystal Skull), as much of it takes place in Europe. It’s also full of delightful action sequences, such as Indy jousting with a Nazi soldier on a motorbike, using a flag pole as a lance. The chemistry between Harrison Ford and Sean Connery is note-perfect, utterly believable in their bickering, their similar intelligence, and their charisma.

It works so well that when Henry Jones, Sr. is shot in the third act, you feel it as much as he does.

And here’s the other reason why I love this movie: this is an amazing depiction of faith.

The grail quest is a part of the Fisher King myth: a chalice (or bowl, or plate) that must be found to heal a dying king, whose fate is shared with the kingdom. Eventually it got tied up with Christian mythology, as the grail was later depicted as the cup Joseph of Arimathea used to catch the blood of Christ as he was crucified.

Indiana Jones, outnumbered by the Nazis pursuing the grail, force him to obtain it to save his father. He takes on the role of Sir Galahad, undertaking certain challenges that test his faith in order to obtain his prize. The first two are trivial: he dodges some spinning blades and walks across a crumbling floor, using his father’s diary as a guide (which is where Henry Jones’s bookishness came in handy!)

But the next challenge is a literal leap of faith: he has to step across a vast chasm, with no bridge or rope to guide him. He has no other choice, because if he refuses to make the leap, his father will die.

Resigned, too afraid to even look, he takes a step … and finds footing on an invisible bridge. (The movie depicts this as some forced perspective painted over a slab, which is unconvincing from almost every angle.)

What inspired this post was a video on Crash Course (hosted by the inimitable Hank Green) about Pascal’s Wager. He describes Indy’s trials to get the grail as a perfect demonstration of philosophical Pragmatism: choosing to believe because it’s the expedient thing to do, until that belief becomes inborn. I’d argue that the grail trials are representative only if you ignore the last test, the one after the leap of faith: choosing the cup.

After the leap of faith, Indiana Jones meets the last caretaker of the grail, a centuries-old knight (who speak English!) who guards a room full of false grails, with the true grail hidden among them. Drinking from a false grail would lead to his death, but drinking from the true grail would give him everlasting life and be able to save his father from his gunshot wound. Indy chooses the right grail (after the villain Sullivan picks the wrong one and ages centuries in the span of seconds). He picks a cup that, with his extensive education in archeology, looks like something a man of Jesus’s talents and time period could have crafted.

I love this scene for several reasons. First, it shows that a leap of faith isn’t the culmination of faith, but only the beginning of a period of sound judgment and rational thought. (Indy didn’t pick one out at random and hope for the best!) Second, Indy becomes more like his father in that moment, ditching his impulsiveness for a moment of insight. Third, to make sure that it’s the right grail, Indy has to drink from it. If he had picked the wrong one, he’d be dead, and his father soon after. He trusted his own judgment, but was willing to risk his own life before risking his father’s.

Indiana Jones loses the grail, on par with every other grail retelling. When they try to take it out of temple where it was held, the floor collapses, and he nearly falls to his death trying to get the grail out. (His love interest does just that moments before, unable to let the grail go.) In the end, it isn’t the grail that matters, but what it’s done for those who matter to him.

It’s an insightful 30’s-era retelling of the grail legend, a great father-and-son story, and a way better film than Temple of Doom. This is my Indiana Jones.