The Curator Fan

I hate quotation. Tell me what you know.

--Ralph Waldo Emerson, Immortality

[caption id=“attachment_52” align=“alignright” width=“207” caption=“Photo by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen”] [/caption]

[/caption]

Unlike many in the fan community, I have an uneasy relationship with fan fiction. I indulged in it a few times during college. I’ve had half a mind to write a fan screenplay of Dune, or Neon Genesis Evangelion, or Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind. I even developed an idea for a sequel novel to the Avatar: the Last Airbender, but with the upcoming Legend of Korra covering similar grounds, I haven’t pursued it.

And I will never write any of the above.

Why?

My writing time is precious, spent only on projects I care about. While I enjoy going back to the well, watching a favorite TV series or reading that one beloved novel, I can’t drink from the same well forever, lest it go dry.

I have many friends who write little but fan fiction. They’ve become curators of the original work in their minds, sometimes when the original creator has long moved on. They are motivated by love: love of the story, love of the creator, love of those who participated in it.

But the community ossifies this fan-created work. It becomes a kind of fan canon – or “fanon,” if you will. If the original creator or a designated caretaker for the work dares to add to the story – I dare say, improve it – fans meet it with hostility of the worst kind. It takes work of special quality to pacify such fans, but even that is not guaranteed. The best that can be hoped for is for the new work to be tolerated, much less appreciated, by fandom.

Our ingrained reactions are that of the stereotype of an overbearing mother. We give so much love to something great in our lives, but that thing isn’t wholly ours, and we are in danger of smothering it.

What if we were in control of our beloved properties? What if the inmates ran the asylum?

Such was the case with Arthurian myth. The kernel of the mythos originated in a historical text, the History of the Kings of Britain, written by an anonymous monk. It contained none of the major arcs we associate with Arthur today: the Holy Grail, Excalibur, the Knights Errant. These were added many years later, by bards and poets retelling and elaborating on the original tale. The flavor of the pseudo-historical Arthur was lost along the way. Several characters were renamed, dropped, added, or modified beyond all recognition. Modern retellings treat the rich source material as a starting point only, taking it in such directions as a feminist deconstruction, a historical farce, and a high school drama.

Such was the case with Arthurian myth. The kernel of the mythos originated in a historical text, the History of the Kings of Britain, written by an anonymous monk. It contained none of the major arcs we associate with Arthur today: the Holy Grail, Excalibur, the Knights Errant. These were added many years later, by bards and poets retelling and elaborating on the original tale. The flavor of the pseudo-historical Arthur was lost along the way. Several characters were renamed, dropped, added, or modified beyond all recognition. Modern retellings treat the rich source material as a starting point only, taking it in such directions as a feminist deconstruction, a historical farce, and a high school drama.

But such fan control doesn’t always end well.

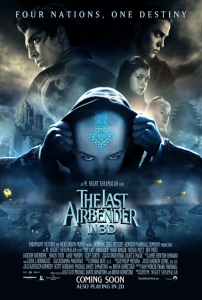

The Last Airbender got off the ground thanks to M. Night Shyalaman’s efforts. His children first introduced him to the show. Like many adult converts, he appreciated it for its emotional range, impressive animation and great humor. Like most of us, he wanted to see the story realized in the biggest canvas available to western society: the silver screen.

The Last Airbender got off the ground thanks to M. Night Shyalaman’s efforts. His children first introduced him to the show. Like many adult converts, he appreciated it for its emotional range, impressive animation and great humor. Like most of us, he wanted to see the story realized in the biggest canvas available to western society: the silver screen.

Like almost all of us, he was woefully unprepared for the task.

Shyalaman had never filmed a big-budget film before Airbender. All of his prior films were based on his original screenplays. His critical reception had been foundering, his earlier quality work seen as a lark. When Paramount agreed to his pitch, they paired him with Frank Marshall and Kathleen Kennedy, two of the most powerful producers in Hollywood, and this undermined his leadership. But more than that, the budget for the film would be substantial – around $150 million – and those paying the bills would have enormous say in how it was made.

However, of the many issues in production, the biggest was Shyalaman’s failure to adapt the story well. He approached it faithfully at first; he remarked that the original screenplay was six hours long. When he was forced to cut down the story (and every writer must murder their darlings), he cut the wrong parts. A good edit can turn a flabby couch potato of a story into a lean sprinter; a bad one can turn it into a mangled corpse.

It was a film that I could only watch drunk, months after its release, in the privacy of my apartment with no one else to witness my shame. I thought Airbender was over. That Korra is in production, that there remain loyal fans who still enjoy the original series and new fans joining their ranks, is a miracle.

Navigating these dire straits between slavish devotion and willful abandonment is treacherous. What is a fan writer to do?

Don’t.

Write something new. Write something remarkable. Remain inspired by what you love, but leave it behind, and find your own place. There is more honor in burying a work as fertilizer in your creative garden than keeping it on a pedestal in a dead flowerbed. (This is why I don’t bag comics. They’re meant to be read, not preserved!)

If you pick any creator – author, writer/director, musician – and dissect them, you’ll find a fan buried beneath. The inspirations for great works is sometimes obvious; watch Forbidden Planet and read Shakespeare’s the Tempest afterwards. Sometimes it isn’t; you have to peer long and hard at the Land Before Time before you’ll see Dante’s Inferno. All of these people, everyone whose works you love, were fans like us once.

I may never write something as moving, captivating and unsettling as Dune was when I first read it. But I can sure try. It’s that desire to find the wonder again that drives me. But re-writing Dune, word-for-word? How dull. Yet that’s exactly what fans expect.